© GrandPalaisRmn (MNAAG, Paris) / image GrandPalaisRmn / distributed by AMF

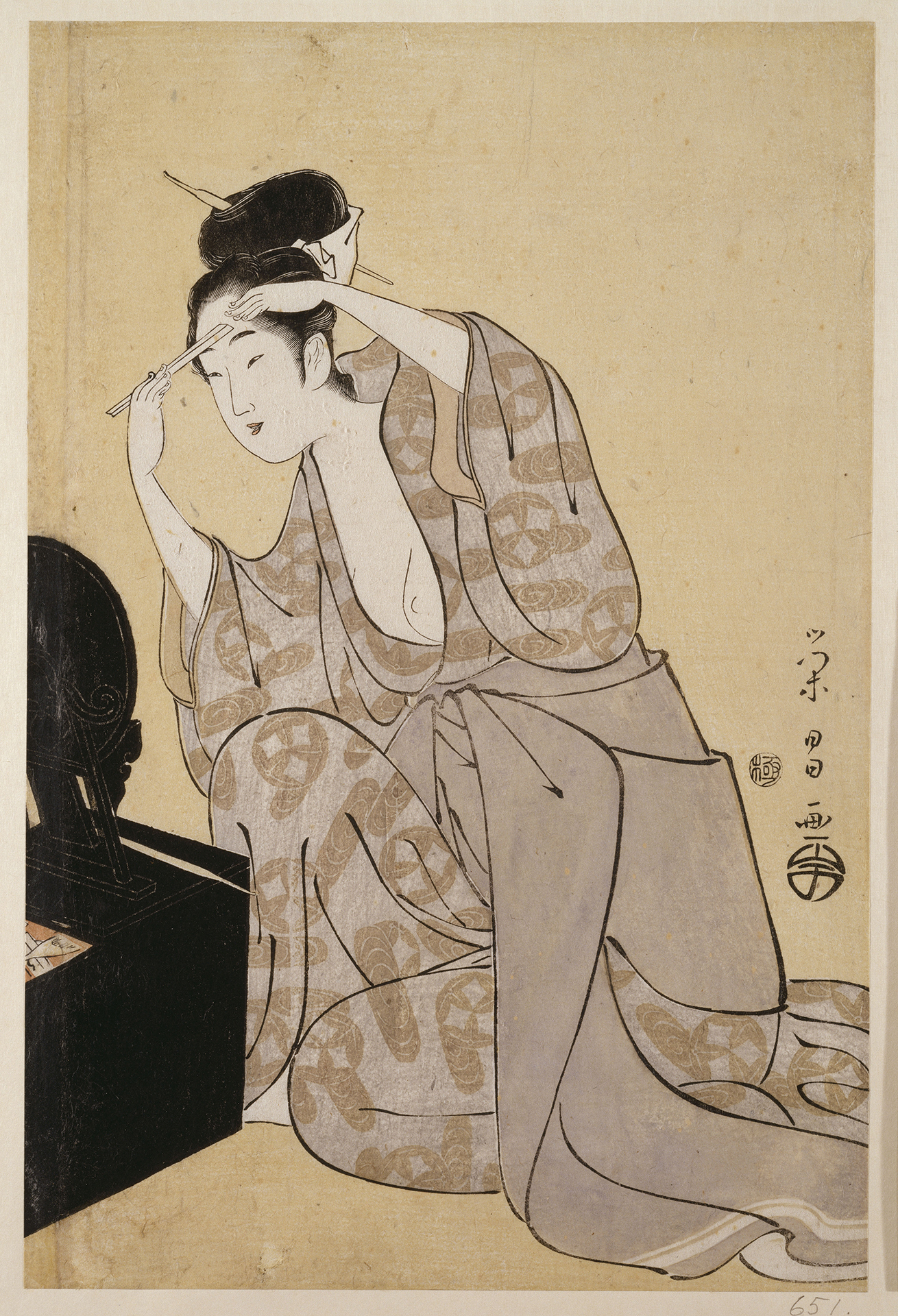

江戸時代中期の浮世絵師、礒田湖龍斎が描く、当時主流だった鏡台。

その姿を映すこの浮世絵は、現在パリのギメ東洋美術館に収蔵。

鏡台に映る、自分と世界の変遷

鏡台――昭和の日本で生まれた私には日常の記憶に絡まる響き。それは日々の家事を終えたママが一段落して向かっている背中の先だったり、化粧品販売員をしていた叔母の家に泊まると布団の敷かれる部屋にあり、化粧品と潮風の混ざった匂いで目覚める夏休みの香り。中学生のとき、初めてアメリカで滞在したホストファミリーのマザーの鏡台はびっくりするほど巨大で、家の中を案内されたときにわざわざ立ち止まり説明を受けた(ただ当時の語学力では何を説明されたのか理解していないが、ワーキングウーマンだった彼女がキメ顔をつくるご自慢の場所だったのだろう)。高校生のときはオーストラリアの滞在先のませた同級生、自分の部屋に鏡台があり、スタイリングを真似したいスターの切り抜きが鏡台のまわりにたくさん貼られ、実践にあけくれていた。その後、移り住んだスウェーデンでは鏡台という家具はあまり見ることはなく、機能的な洗面台以外に、鏡は居間や廊下で頻繁に見受けられ、インテリアの要素として花器や燭台などと合わされることが多く、日照時間差の大きな北欧では、明るい日差しも、暗い蠟燭の灯りも漏らさず空間に光を多く映し込もうとするインテリアの知恵だった。

鏡台という家具が登場し一般化するまでの派生と過程を考えてみると、人がどのように自然光とそれを反射する素材の関係性を捉え、それが暮らし方に反映されてきたのかが見えてきて面白い。

鏡とは画像を反射する物体。現在の大量生産のできるフロートガラス製の鏡が完成し一般市民に普及したのは20世紀初頭、そこに至るまで人々は何千年もの間、石、金属、ガラスなどさまざまな材料から鏡を製造したが、仏具や奉納品、貴族の化粧用など使用は限られていた。でも最も古いものは誰でも使えた天然の鏡。水面に映り込んだ景色、月明かり、そこに自分自身を映し込むことで、人間と世界が共生しているという現実を心情として捉えることができたのではないでしょうか。つまり自己の実在をまわりの風景と合わせて理解するということは、自分自身の外見と内面の関係性を理解し、それがどう他者に影響するかということに気づくこと。そしてその気づきこそがセルフケアであり、人間の興味を大いに搔き立てたことでしょう。

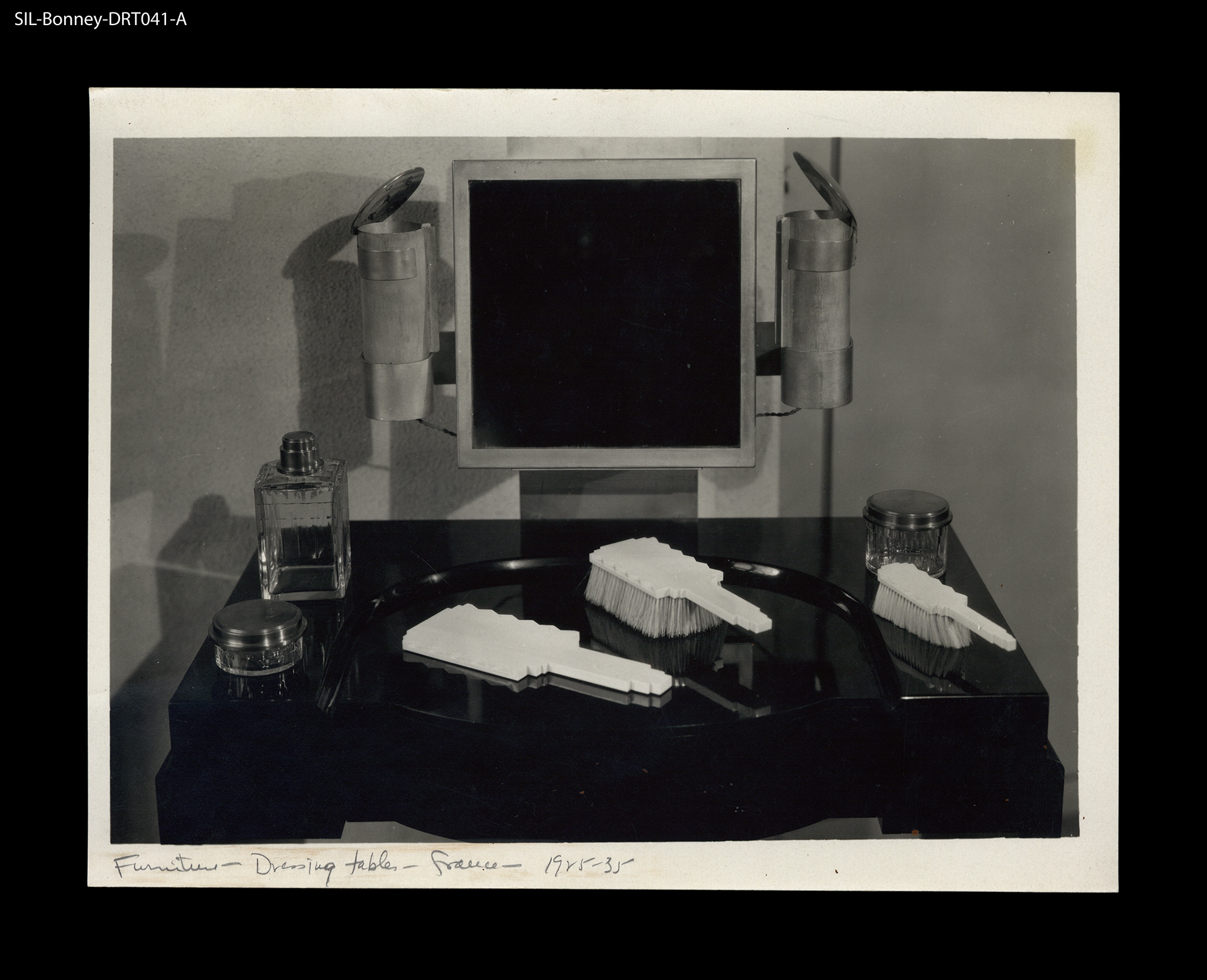

© The Regents of the University of California,The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

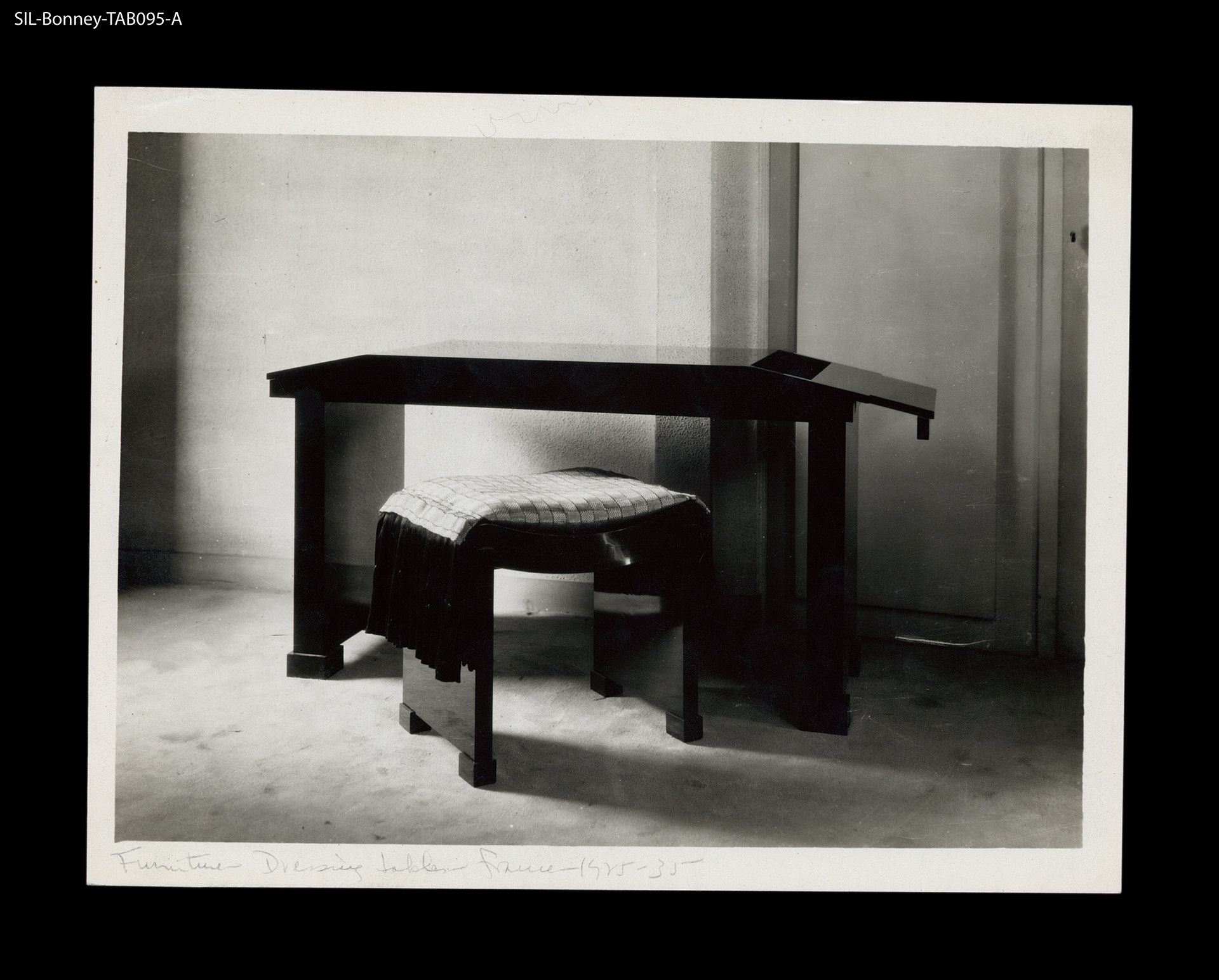

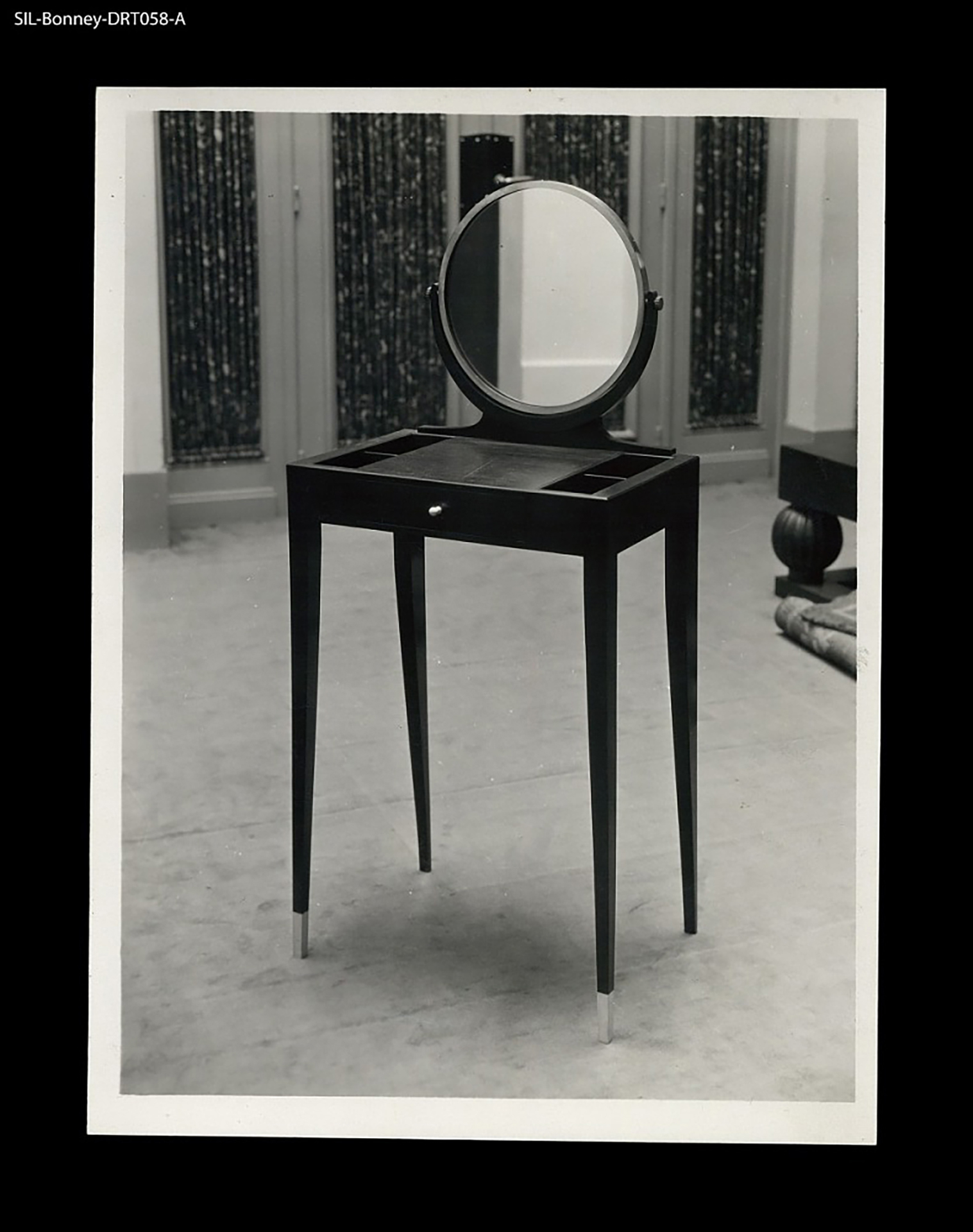

パリのサンジェルマン・デ・プレに佇むガラス・ブロックの建築「ラ・メゾン・ド・ヴェール」、通称「ガラスの家」。その設計で知られる家具デザイナー、ピエール・シャローが手掛けた鏡台。

© The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license

アール・デコを代表するフランス人家具デザイナー。富裕層に評判を呼び、ラグジュアリーな鏡台の代表作。

Photography Ruby Woodhouse for Abel Sloane 1934

「少女のための寝室」という作品の一部としてデザインされた鏡台。1924 年、アムステルダムの家具店で展示されたとき、美しいシルエットが人々を魅了したと言われている。

天然の鏡の話に戻ると、水面は風が止んだときだけほぼ静止し、綺麗な画像を映し出すが、水は淀みなく、また人間の心もみかけも常に変化するもの。鏡の発明とは、セルフケアのためにその瞬間を逃したくないという欲望が駆り立てた発明品ともいえます。またそのときを過ごす場所として、どこにどう鏡を置くのかということが重要になってきたのです。元々は水のあるところに人間が寄っていったのでしょうが、瓶に水を張ったり、金属や石を磨いたりと自分の手元に置けるような努力が行われましたが、映し出すためには光が不可欠でした。そのため、映りをよくするために、光のあるところに持っていきやすい手鏡などの動かしやすいサイズが主流でした。その後、近代になると鏡のクオリティも上がり、電気の普及により自然光よりも安定した光が得られるようになると、鏡を置く位置は固定されていても困らないようになっていきます。また、同じ頃、洗濯機、炊飯器など家事を劇的に変える商品がたくさん開発されます。それらはこれまでの家事の時間を短縮し、女性に時間のゆとりを生み出したのです。つまり、鏡台に向かう時間、セルフケアという祝福すべき新しい時間の獲得。急速に家庭に普及した鏡台というのは、このような近代社会における個人化を象徴する家具であった気がします。現在では変化していますが、役者などを除けば、鏡台は女性用という稀な性別限定感をもった家具でもありました。そんな中、1985年に建築家の伊東豊雄さんが当時のスタッフであった妹島和世さんの協力で「東京遊牧少女の包(パオ)」というプロジェクトを発表しました。東京に暮らす独身女性にとってレストランはダイニングルーム、ブティックはワードローブ、コインランドリーは洗濯機、つまり都市空間の総体が住処であり、家という概念を解体し、遊牧民のように都市で暮らす女性のための断片的な空間を提案、その中に「おしゃれする家具」として鏡台がありました。ここでも鏡台は女性を象徴する家具として存在しますが、街の中に軽やかに開放されました。

以来、住宅や家具の小型化や軽量化、携帯電話のカメラがミラー代わりになり、鏡台という存在がいささか古めかしく感じる家具になってしまいましたが、そんな中でも鏡本来の力を引き出す自然光の力を理解してデザインされた鏡台は機能的にも本質的にも現代に通じる美しさを保っています。私自身は鏡台をもっていませんが、未だ35年ぐらい使っているコンパクトミラーで事足りています。どの国に移り住んでも、旅行先でも晴れた日には窓辺で、採光が足りない日には明かりの下に行って眉毛を整えます。アンドレ・プットマンの鏡台はそんなシンプルさを反映した流行に左右されないマスターピース。

(椅子:ピエール・ストーデンマイヤー、版画:アンドレア・ブランジ)

Courtesy of Marie-Anne Derville (Interior Design / Curation) Photography © Matthew Avignone

フランスのインテリアデザイナー、アンドレ・プットマン。独特なエッジーさとエレガンスを兼ね備えたデザインは、ホテルや美術館などで話題を呼んだ。この鏡台は、鏡を閉じればデスクとなるミニマルなデザイン。彼女の作品の中で特別な存在感を放つ。

写真:大橋富夫

バブル期の東京、ノマドのように街を遊牧する少女のために提案された建築空間。ファミリーレストランや 24 時間営業のコンビニが生活の一部となった現代においても、独り暮らしの女性の「ねぐら」に残った鏡台。

また鏡に向かう場所というのは間接的に自分や世界を眺めることでもあるのです。鏡は現実と心理を映し出します。鏡に対する魅惑は『ドリアン・グレイの肖像』(オスカー・ワイルド著、1890年)や『白雪姫』(ドイツ民話『グリム童話』収載、1812年)などの多くの文学作品や民話などの中でも心理的装置として描写されてきましたが、私が好きなのは夏目漱石の『吾輩は猫である』(1905~06年)の描写、「鏡は己惚の醸造器であるごとく、同時に自慢の消毒器である。もし浮華虚栄の念をもってこれに対する時はこれほど愚物を煽動する道具はない(引用)」。時代と共に人と暮らしの時間のあり方は変化し続けているけれど、鏡とはいつまでも自己と世界の関係性を映しこむ天然のものなのだろう。どんなに忙しい日々が続いてもときには鏡に向かわなくては。

Chair: Josef Franz Maria Hoffmann (Thonet) 1908

Table: LICHT gallery Bespoke 2019

Mirror: LICHT gallery Bespoke 2025

SHISEIDO TechnoSatin Gel Lipstick

SHISEIDO HANATSUBAKI HAKE Polishing Face Brush

横山いくこ / 香港の美術館 M+デザイン&建築部門リード・キュレーター、ライター。専門はデザインや建築、工芸分野であり、21年間スウェーデンに在住した経験をもつ。ICAM国際建築美術館連盟執行役員、文化庁文化審議会専門委員も務める。

Mirror, Mirror(From Hanatsubaki No.832 "care")

2025.3.18

Text / Ikko Yokoyama

The word “dressing table” is intertwined with my memories of everyday life as someone born in Showa-era Japan. I glimpsed my mother’s dressing table over her shoulder when she sat down at it after finishing the day’s housework; when we went to visit my aunt over the summer holidays, there was a dressing table was in the bedroom where I woke up each morning to the combined scent of the sea breeze and the makeup my aunt sold at her cosmetics counter. In junior high school, when I visited the United States for the first time, I was astonished by the sheer size of my host mother’s dressing table. She paused in front of it during my tour of the house to offer a detailed explanation. My facility with the language was still limited then, but in retrospect I imagine she was proud to have such a splendid place to put on her face before heading out to work. At a home school homestay in Australia, my precocious host sister—despite being the same age as me—had a dressing table in her room where she would sit and tirelessly strive to replicate the looks in the cut-out pictures of stars that ringed the mirror. Later, I moved to Sweden, where dressing tables are less common and mirrors are placed not just functionally over washbasins but also in living rooms and halls, often combined with interior design elements like vases or candlesticks. Northern Europe’s dramatic differences in day and night length have given rise to a common wisdom of interior design in which dazzling sunlight and the dim flicker of candles are both diligently captured and guided to the corners that need them most.

Pondering the origins of dressing table, and the process by which it became a standard piece of household furniture, helps elucidate the relationship between the natural light humans crave and the materials that reflect it. It is fascinating to see how this has affected our everyday lives.

A mirror is an object that reflects images. Today’s mass-produced float mirrors were not perfected and made available to everyday citizens until the early twentieth century. People were making mirrors for thousands of years before this, using materials such as stone, metal, and glass, but these mirrors had strictly limited application as Buddhist artifacts, religious offerings, and items used by nobles at their toilet. By contrast, the oldest mirror of all, is completely natural and available for everyone to use. Perhaps it was seeing our own images amid the landscapes and moonlight reflected on the face of the water that helped humanity realize, on an emotional level, that we coexist with nature. To understand your existence in conjunction with the scenery is to grasp the relationship between your external appearance and inner world and realize the effect it has on others. That realization was itself self-care and surely stirred up great interest in humanity at large.

On a still day, calm waters mean clear reflections in these natural mirrors. But water is constantly in motion, and our hearts and appearances are fluid, too. The invention of the mirror could be attributed to a desire to preserve those moments for the sake of self-care. This, in turn, raises the important question of where and how to place mirrors to create spaces for spending those moments. No doubt humans originally gathered around the water itself, but the desire to keep mirrors close at hand inspired the invention of water-filled vessels and polished metal and stone. There can be no reflection without light, so most mirrors were small and portable enough to be taken where the light was. As modernity progressed, mirrors improved in quality, and electrification resulted in artificial light that was readily available and stabler than its natural counterpart. Mirrors came to adopt fixed locations as a result. During the same period, inventions like the washing machine and the rice cooker revolutionized housework, slashing the time and effort required and relieving some of the pressure on women’s daily schedules. This, in turn, gave women time to sit at their dressing table, creating a new moment devoted to self-care. The boom in popularity of the dressing table in everyday houses, I believe, was inspired by the way it symbolizes individualization within modern society. The dressing table continues to evolve today, and remains one of the few pieces of furniture strongly associated with gender: with the exception of actors and the like, only women use dressing tables. This was the context in which, in 1985, architect Toyo Ito, in collaboration with Kazuyo Sejima, who was then one of his staff members, unveiled their Pao for the Tokyo Nomad Girl project. Single women living in Tokyo used restaurants as dining rooms, boutiques as wardrobes, laundromats as washing machines—in short, they made the urban space as a whole their residence. Ito and Sejima’s project deconstructs the concept of the house, proposing in its place a fragmented space designed for women who live like urban nomads, and even in this context the dressing table is present as “furniture for dressing up.” Though still coded female, the dressing table has casually been released into the streets.

As homes grow smaller, furniture grows lighter, and we turn increasingly to phone cameras instead of mirrors, the dressing table has come to feel rather old-fashioned. Nevertheless, when designed with an understanding of natural light and its ability to draw out the innate power of mirrors, dressing tables retain their functional and essential beauty even today. I do not own a dressing table myself; the compact I have used for some 35 years is still sufficient for my needs. Whichever country I find myself residing or traveling in, I sit by the window on sunny days, or under the light fixture on gloomy ones, to adjust my eyebrows. Andrée Putman’s dressing tables are masterpieces that reflect this simplicity without bending to the whims of fashion.

The place where we sit at our dressing table is also our vantage point for regarding—albeit indirectly—ourselves and our world. A mirror reflects both reality and our state of mind. The human fascination with mirrors is evident from their depiction as psychological apparatus in countless stories, from Oscar Wilde’s 1890 novel The Picture of Dorian Gray to the German folk tale of Snow White published by the Grimm Brothers in 1812. My favourite description of a mirror, however, can be found in Natsume Soseki’s novel I Am a Cat, serialized from 1905 to 1906, in which the titular cat remarks (in Aiko Ito and Graeme Wilson’s translation): “A mirror is a vat for brewing self-conceit, yet, at the same time, a means to neutralize all vanity. Nothing shows up the absurd pretensions of a show-off more incitingly than a mirror.” Even as our way of life evolves with the times, mirrors will always remain unchanged in essence from those original, natural mirrors that reflected our relationship with the world back to us. No matter how busy we get, we must make time to sit down before the mirror.

(Translation Matt Treyvaud)

Captions:

Isoda Koryusai (1735–1790), “Woman grooming her eyebrows”

Isoda Koryusai was an ukiyo-e artist of the mid–Edo period. This print, currently in the collection of the Musée Guimet in Paris, depicts one of the dressing tables that were in fashion at the time.

Two dressing tables by Pierre Chareau (1883–1950)

Dressing tables crafted by Pierre Chareau, a furniture designer known for his work on the renowned Maison de Verre or “Glass House” in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Paris.

Dressing table by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1879-1933)

A French furniture designer who epitomized Art Deco. His luxurious dressing tables were highly regarded by the wealthy elite of the time.

Dressing table by Hendrick Wouda (1885–1946)

This dressing table was designed as part of a set entitled “Bedroom for a Young Girl.” Its exquisite silhouette captivated visitors when it was displayed at a furniture store in Amsterdam in 1924.

Dressing table by Andrée Putman (1925–2013) (chair: Pierre Staudenmeyer, print: Andrea Branzi )

Andrée Putman was a French interior designer whose eye-catching work for hotels and museums combined a unique edginess and elegance. This dressing table has a minimal design, becoming a desk if the mirror is closed. Even among Putman’s oeuvre, it has a particularly special presence to it.

Toyo Ito (1941–), “Pao for the Tokyo Nomad Girl” (1985)

Photograph: Tomio Ohashi

An architectural space designed for the young women who lived like urban nomads during Bubble-era Tokyo. Even with family restaurants and 24-hour convenience stores part of their lives, dressing tables could still be found in these one-woman dens.

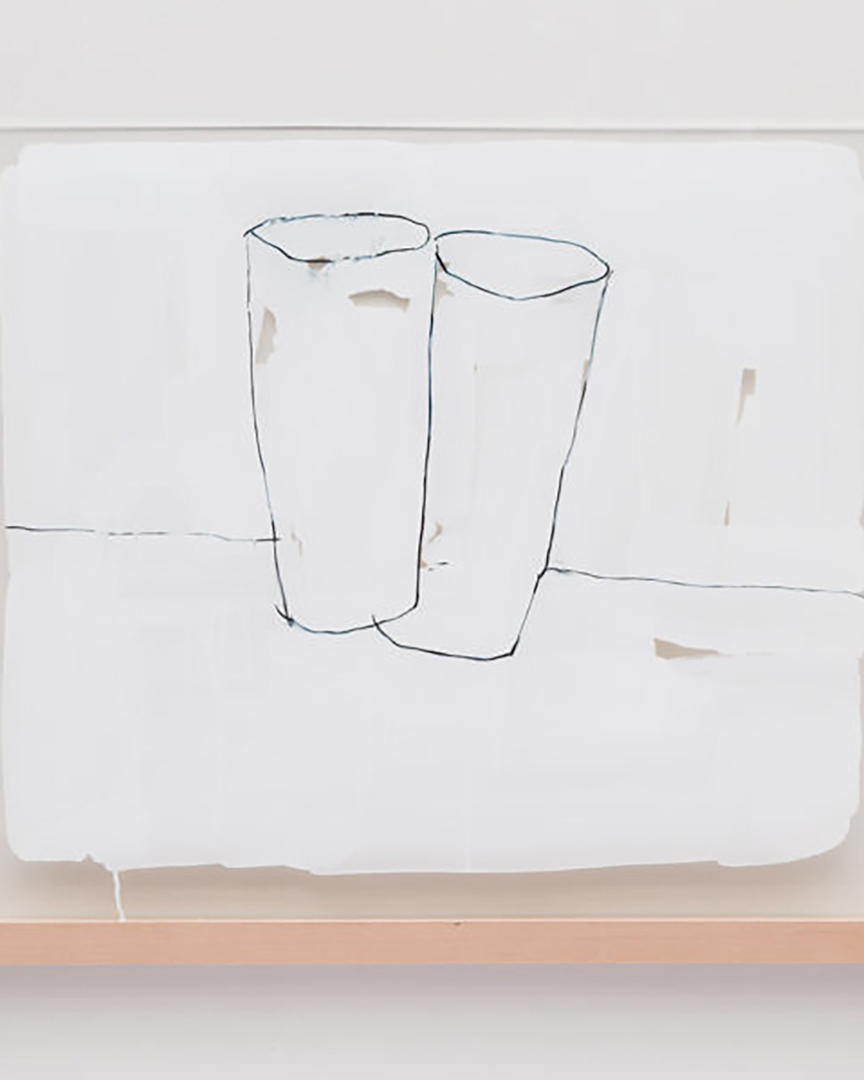

Contemporary Dressing Table

This portable dressing table devised by LICHT gallery can be moved to where the light is even in cramped spaces. The mirror can be detached and stowed when necessary, and it combines usability with beauty in a way suited to contemporary lifestyles.

Ikko Yokoyama is the Lead Curator of Design and Architecture at M+, a museum in Hong Kong, as well as a writer. Specialising in design, architecture, and crafts, she was based in Sweden for 21 years. She is an executive committee member of the International Con-federation of Architectural Museums (ICAM) and an expert member of the Council for Cultural Affairs under the Agency of Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan.