銀座――この魅力的な街は、多くの人々にとって、特別な瞬間や記憶に残る場所となっています。親に手を引かれて足を踏み入れたデパート、マスターのこだわりを感じる喫茶店、初デートで訪れたレストラン。どれもが、この街の独特の雰囲気と結びついています。

連載「銀座・メモワール」では、森岡書店代表、森岡督行さんがナビゲーターとして登場します。多様なゲストが織りなす銀座の豊かな物語を共有し、銀座の多面性とその普遍的な魅力に焦点を当てます。連載を通じて、銀座の隠れた魅力と多彩なストーリーに触れ、新たな価値を一緒に発見しましょう。

連載4回目のゲストは、草木に仕える「花士(はなのふ)」というちょっと変わった肩書をもつ珠寳(しゅほう)さんです。

銀閣寺の名で知られる慈照寺の初代花方教授として、10年間にわたり足利義政時代の花を研究した珠寳さんは2015年に独立。現在は国内外を舞台に、自然や神仏に花を献ずるなど、花を通じて多岐にわたる活動を続けています。

この日は、1932年に竣工した銀座を代表するレトロ建築「奥野ビル」の一室にできた森岡書店の新しい事務所でお花を立ててくださいました。

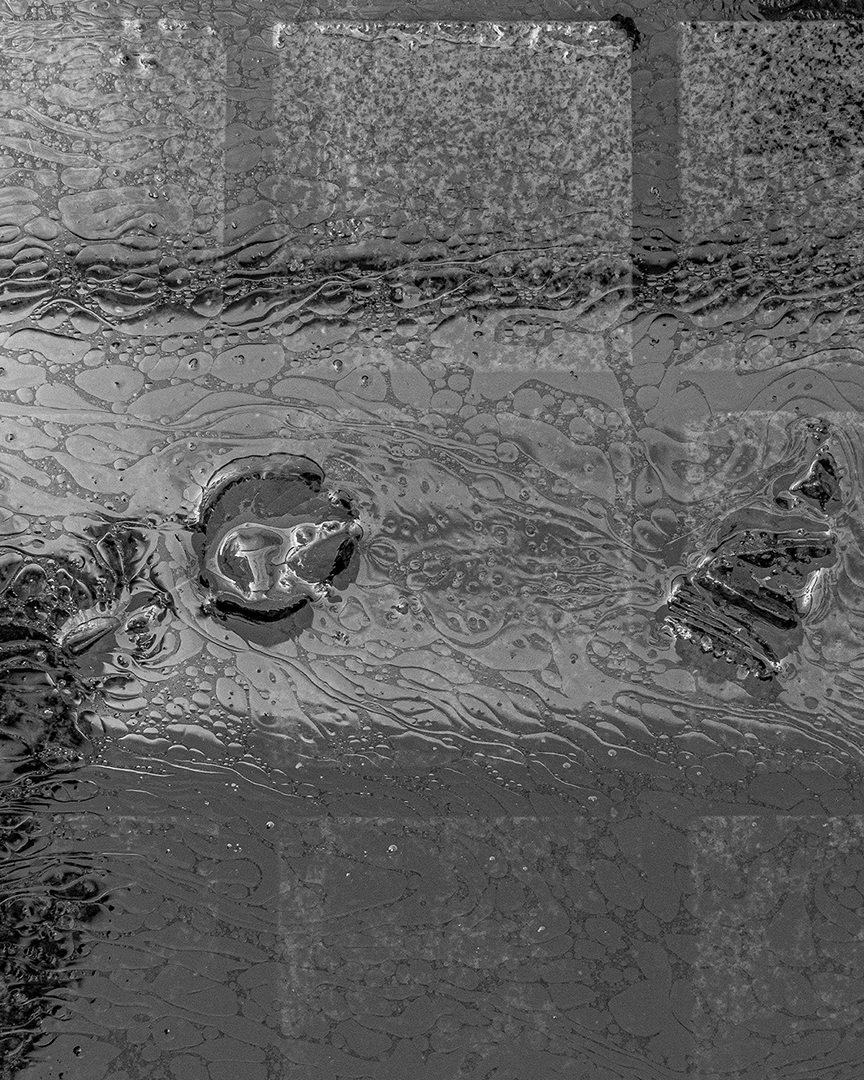

花器に仕込まれるこみ藁〔お米の藁を乾燥させて束にしたもので花を留める道具〕、ハサミで思いきりよく切られていく枝、なみなみと注がれる水。儀式のような静謐さをもって執り行われる「たて花」は、瞬く間に部屋の雰囲気を変えていきます。

珠寳さんが花を立てる姿は凛とし、動作に一切のむだはありません。しかし、その日どんな花を立てるか、あらかじめ決めているわけではないと珠寳さんは言います。空間と花器があればおのずとやることは決まるのだ、と。

そんなたて花を極めたかに見える珠寳さんにも、師匠について鞄持ちをしていた時期がありました。そして、その当時の強烈な思い出は、銀座の街にまつわるものでした――。

花の世界の“二巨頭”が銀座で交わした歴史的会話

森岡 珠寳さんは銀座3丁目の「野の花 司」とご縁があったとか。

珠寳 はい。岡田幸三先生〔昭和を代表する花人/古典花道の研究家〕の鞄持ちをしていたときに一緒に伺っていました。古美術商に行く前や後に立ち寄られていました。当時はついて行くのに必死で、どこのお店だったかは覚えておりませんが。

森岡 岡田さんと食事をしたりとか、銀座にまつわる思い出はありますか?

珠寳 ひとつ強烈な思い出があります。岡田先生のおともで、銀座の古美術商に立ち寄り、その後銀座の大通りに面した2階にある小さなギャラリーに行ったときの記憶です。書家の方の展覧会だったと思いますが、ギャラリーの名前は記憶にありません。そこにあったベンチに偶然、中川幸夫さん〔前衛いけばな作家〕が座っておられました。古い付き合いのおふたりだとは思うんですが、先生はフッと見るだけで別に挨拶されるわけでもなかったんですが、中川さんが突然「今日本のいけ花が大変な方向にいっているから、どうぞ牽引していってください」とおっしゃって。岡田先生はただ頷いておられた。花の世界で、西の岡田、東の中川といわれた二巨頭が並んだ光景で、今でもよく覚えています。

森岡 「日本のお花を頼む」ということだったのかもしれないですね。立場の違いはあったかもしれないですけども、おふたりが目指したものは似ていたんでしょうか?

珠寳 伝統と前衛、ことばのうえでは対極にあるように聞こえますけど、きっと同じ本質を見つめておられたと思いますし、私もやはりそういう指導を受けていました。だから、お花のいけ方や立て方で、こうしなさいという指導は一切ありませんでした。生と死を見つめておられたおふたりだと思います。いけ花の原点立返ると定型がない。当然ですよね、生き物が相手ですから。

指先を頼りに、草木の“声”を聴く

森岡 目の前で花を立てていただいて、今感激しています。身が引き締まりますね。椿に傷があることにも胸を打たれました。完全と不完全が同居している感じがして。

珠寳 自然界の命ある生き物としてのお花を、人間や動物を見るときと同じ思いで見ています。ですから、完璧なものだけではなく、盛りを過ぎたものだったり、虫に食われたものだったり、これから成長する段階の草木も美しいと感じて分け隔てなく使います。そこにいろんな時間軸が入ってくるんです。

森岡 花のなかに過去・未来・現在があって、たて花はそういったいくつもの時間と空間を集約するようなものなんでしょうか?

珠寳 そうです。はじめに柳を1本立てた段階で、いろんな時空とつながるようなイメージです。

森岡 なるほど。柳というのは銀座らしいですね。

珠寳 というのも本来、花瓶のなかの見えないところが大事なんです。いちばんの見どころも、花瓶の口から数センチの“水際”といわれるところ。お花を立てるときは、ここにいちばん集中します。水際を見てから、目線を上げていって全体の花の姿を見る。水際は見えない世界から見える世界、彼方から此方への出入り口なので、エネルギーが立ち上がってくる重要な場所なんです。

森岡 “こみ藁”に立てる枝の根元を細く削ったり切ったりされていた作業も印象的でした。

珠寳 あれは、木密(こみ)に入るところをできるだけ細くして中心を取ってるんです。そうするとスッと素直に立ち上がって、枝本来の姿が生かされる。今、枝やお花の形を変えてデザインしていく用語として「ためる」が使われていますが、本来は、花には完璧な自然の美しさが備わっているので、花の姿はそのままに、花瓶の下の目に見えない部分に歪みがあれば調整します。このことを「ためる」といいます。いけ花の起源に遡れば遡るほど、そういう考え方で花を扱っています。

森岡 今日はたくさんお花をご用意いただきましたが、すべて使われるわけではないんですね。何を手がかりにお花を選んでいるのでしょう?

珠寳 「今日はこういうお花を立てよう」というのは全く頭に置かずに来ています。現場で皆さんとお会いして、空間と花瓶があるとおのずと決まっていく。お花が「はーい、私!」と言ってくる感じ(笑)。椿も最初は蕾のものを手にしたんですけれど、立ててみるとどうも違和感があって、結局この開ききった椿にしました。なるべくお花は見ないようにして、指先で情報を取るようにしています。

森岡 目では見ないんですか?

珠寳 目で見すぎると、ビジュアルに惑わされるというか、好みや情に流されて翻弄されちゃうんですね。ですから、先ほど申し上げたように、花瓶の下の歪みを整えるにはどうすればいいか、指先を頼りにして情報をもらうんです。切るときも枝から「ここです」というのが伝わってくるので、「はい」と言ってそれに従います。

森岡 お花の声を聞いているってことですか?

珠寳 実際に聞こえるわけじゃないんです。たぶん訓練だと思います。これまで数えきれないくらい稽古していますので、経験上“ここ”というのがピンポイントでわかる。でも、たまにお花(私自身)を信じられないときがあります。そんなに短く切って大丈夫かな?って。でも、それでちょっと長めに切りますと、やっぱり違うんですね。それで「あ、ごめんなさい」と切り直したりしますね。

後篇につづく…

珠寳 花士

2004年から2014年まで慈照寺(銀閣寺)にて初代花方を務め、義政公時代の「座敷飾りの花」「室礼」の顕彰、江戸中期に創流された「花術 無雙眞古流」の再生に10年間従事。慈照寺研修道場にて講座の企画、運営をし、「平和と文化」をテーマに国際交流を企画、実施。

2015年に青蓮舎を設立し、草木に仕える花士として、大自然、神仏、人に花を献ずることをライフワークとし、花朋の会では花を通して豊かな生活時間を提案している。また、能楽、現代美術、音楽、工芸、建築など、伝統から現代の国内外のクリエーターと協働。

2024年からは一般社団法人游神会を設立し、代表理事を務める。精神をおおらかに遊ばせた室町時代の阿弥系のたて花から時代を追って、「いけばな」の精神性、美と術を探求し、記録をとる事業を主軸とする。いけばなのはじまり、成立、展開、関連する学問、芸術、芸能などを知る場を作り、次代をになう人材育成に努める。主な著書:

『銀閣慈照寺の花 造化自然』(淡交社)

『一本草』(徳間書店) 他

森岡 督行

1974年山形県生まれ。森岡書店代表。文筆家。『800日間銀座一周』(文春文庫)、『ショートケーキを許す』(雷鳥社)など著書多数。 キュレーターとしても活動し、聖心女子大学と共同した展示シリーズの第二期となる「子どもと放射線」を、2023年10月30日から2024年4月22日まで開催する。

https://www.instagram.com/moriokashoten/?hl=ja平岩壮悟

編集者/ライター1990年、岐阜県高山市生まれ。フリーランス編集/ライターとして文芸誌、カルチャー誌、ファッション誌に寄稿するほか、オクテイヴィア・E・バトラー『血を分けた子ども』(藤井光訳、河出書房新社)をはじめとした書籍の企画・編集に携わる。訳書にヴァージル・アブロー『ダイアローグ』(アダチプレス)。

www.instagram.com/sogohiraiwaナタリー・カンタクシーノ

フォトグラファー

スウェーデン・ストックホルム出身のフォトグラファー。東京で日本文化や写真技術を学び、ファッションからドキュメンタリー、ライフスタイルのジャンルで活躍。https://www.instagram.com/nanorie/

Ginza Memoir #4 Part 1 "A Page of History, Witnessed in Ginza"

2024.10.17

Text / Sogo Hiraiwa

Photo / Nathalie Cantacuzino

Ginza is a fascinating town, frequently linked with special moments and fond memories. Visits to department stores while holding tightly to a parent’s hand, afternoons in old-fashioned cafés run by one-of-a-kind characters, first dates in special restaurants . . . Ginza is a place like no other.

Hanatsubaki’s “Ginza Memoir” series, hosted by Yoshiyuki Morioka of the iconic Morioka Shoten bookstore, explores the multifaceted nature and universal appeal of Ginza through interviews with guests from a wide variety of fields. With Morioka as guide to Ginza’s hidden charms and diverse narratives, new discoveries await around every corner.

Our fourth guest for “Ginza Memoir” is Shuho, who bears the slightly unusual title of hananofu, describing someone who tends to plants.

As the first general manager of flower affairs, or hanagata, at Jishoji—known as the “Temple of the Silver Pavilion”—Shuho spent a decade studying flower arrangement during the time of Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436–1490) before going independent in 2015. She is now active in Japan and around the world, particularly with her work of offering flowers to nature and to the divine.

On the day of our interview, she prepared a standing arrangement of flowers, known as tatehana, in the new office of the Morioka bookstore in the 1932 Okuno building, one of Ginza’s best-known retro structures.

The komiwara, a bundle of dried rice straw placed in the vase to hold the flowers; the stems briskly cut by shears; the water filling the vessel to the brim . . . Shuho worked with a ritual-like poise and tranquillity that changed the mood of the room completely. Not a single wasted movement was evident. However, she says, she never arrives at such an event having already decided how to begin her arrangement. Once the space and vessel are provided, the rest decides itself.

But even Shuho, today a master in her own right, was once an apprentice tasked with carrying the bags of a teacher. And one of her most striking memories from those days was of an encounter right here in Ginza . . .

A Historic Encounter in Ginza Between Two Giants of the Flower World

Morioka: I believe you have some connection to the florist Nonohana Tsukasa in Ginza Sanchome.

Shuho: Yes. I visited the store as a student assistant to Kozo Okada [one of the most renowned flower arrangers of the Showa period, and a researcher of the classical Way of Flowers]. We dropped by either before or after visiting an antique store, but at the time I had my hands so full simply keeping up that I don’t remember which store it was.

Morioka: Do you have any memories of Ginza from that period? Meals with Okada, for example?

Shuho: I do have one very vivid memory. Once, after visiting an antique store, Sensei and I stopped by a small upstairs gallery overlooking Ginza Dori. I believe it was a calligraphy exhibition, but I don’t recall the gallery’s name. [Avant-garde ikebana artist] Yukio Nakagawa happened to be sitting on the bench there. The two men had known each other for a long time, but Sensei simply glanced at him without saying a word. Then Nakagawa said, “Ikebana is heading in a terrible direction in today’s Japan. Please take the lead.” Sensei remained silent, but acknowledged this with a nod. People used to speak of the world of flower arrangement being “Okada in the west and Nakagawa in the east,” and I can still remember the sight of those two titans side-by-side.

Morioka: It sounds as if he was passing the torch of Japanese flower arrangement to Okada. Their positions may have been different, but did they share similar goals?

Shuho: Tradition and the avant-garde sound like exact opposites, but I believe both of them perceived the same essence, and that was certainly the sort of instruction I received. I was never told “You must do such-and-such” when practicing ikebana or tatehana. Both masters had their eyes fixed on life and death. When you return to the starting point of ikebana, there are no set forms. This is only logical, of course, when living beings are concerned.

Feeling the Voice of the Flowers Through Her Fingertips

Morioka: Watching you create that tatehana arrangement just now was a deeply moving experience. It made me sit up straighter without even realizing it. I was also struck by the scar on the camellia, which seems to suggest the coexistence of perfection and imperfection.

Shuho: Flowers are living beings in the natural world, so I view them just as I do humans or animals. This means that I do not restrict myself to “perfect” flowers. I see beauty also in flowers that are starting to fade, or have been nibbled by insects, or are not yet fully mature, and use them just as readily. This brings the axis of time into the arrangement in various ways.

Morioka: The flowers contain past, present, and future. Does this mean that tatehana is a way of uniting disparate times and spaces?

Shuho: Yes. From the very first willow branch, the arrangement is connected to space-time in various ways.

Morioka: I see. Using a willow feels appropriate for Ginza, too.

Shuho: Well, the important thing about the arrangement is the unseen parts inside the vessel. Even the part most worth seeing is the waterline a few centimetres from the vessel’s mouth. This is what you focus on when arranging the flowers—you begin from the waterline, then raise your line of sight to take in the arrangement as a whole. The waterline is the threshold between the unseen and the seen—the other world, and our world. This makes it a nexus of energy.

Morioka: I noticed how carefully you scraped and cut the base of the boughs you put into the komiwara.

Shuho: I make the ends that go into the komiwara as thin as possible to keep them centred. That allows them to stand straight up, and preserves their innate nature. The word tameru is used today to refer to reshaping boughs and blossoms to suit a planned design, but flowers already have a perfect natural beauty, so I keep them as they are and make any needed adjustments invisibly, below the waterline. This is the meaning of tameru. The more closely your approach the origins of ikebana, the stronger the influence of this idea becomes on your treatment of the flowers.

Morioka: You prepared many flowers for today’s event, but I notice you do not use them all. What do you rely on when choosing which to use?

Shuho: I always arrive without any preconceived idea for the arrangement. After meeting the other people present and considering the space and the vessel, the matter decides itself. The flowers seem to call out, “Here I am! Use me!” You might have noticed that I picked up the bud-like camellias first, but when I added them to the arrangement something felt off, so ultimately I used the camellias in full bloom. I try to gather information with my fingertips, looking at the flowers as little as possible.

Morioka: You don’t use your eyes?

Shuho: Overusing your eyes increases the risk of being distracted by the visual side of things, or swept away by preferences and emotions. I use my fingertips to gather the information I need, such as how to arrange the parts of the bough below the waterline as I described earlier. When I cut, the boughs and stems seem to tell me, “Here,” and I simply obey.

Morioka: Do you mean that you hear the flowers speak?

Shuho: I don’t actually hear them. I think it’s more a matter of practice. I’ve practiced more times than I can count, and so my experience tells me exactly where “here” is. Even so, there are times when I doubt the flowers [i.e., myself]—Should I really cut it that short? But when I try cutting it a little longer, I see that the original location was actually correct, so I apologize and cut it again.

Continued in Part 2

Hananofu Shuho

From 2004 to 2014, acted as first general manager of flower affairs at Jishoji (the Temple of the Silver Pavilion), spending a decade showing how flowers were used to decorate rooms in the age of Ashikaga Yoshimasa and reconstructing the Muso Shinko school of flower arrangement founded in the mid-Edo period. Planned and hosted workshops at the temple’s research centre, and planned and executed international exchanges around the theme “peace and culture.”

In 2015, established the Seirensha and embraced her life work as a hananofu of offering flowers to nature, the divine, and people, promoting richer lifestyles through flowers via Kaho no Kai gatherings. Also collaborates with traditional and contemporary creators in Japan and around the world in fields such as Noh, contemporary art, music, crafts, and architecture.

In 2024, established the Yushinkai NPO and became its representative director. The organization is chiefly concerned with tracing the history of tatehana from the Ami tradition of the Muromachi Age, which allowed the spirit to play in serenity, and researching and recording the spirituality, art, and technique of ikebana. Strives to create opportunities for learning about the beginning, establishment, and development of ikebana, along with related fields of study, art, and performance, and to cultivate the next generation of practitioners.Major published works:

Flowers of Jishoji of the Silver Pavilion: Creative Nature (Tankosha)

Ippongusa: A Single Stem (Tokuma Shoten)https://www.hananofu.jp/ja/top/

Yoshiyuki Morioka

Born 1974 in Yamagata. Head of the Morioka Shoten bookstore. Writer. Published books include Around Ginza in 800 Days (Bunshun Bunko) and Forgiving the Shortcake (Raichosha). Also active as an art curator, with recent shows including Children and Radiation, the second stage of an exhibition held jointly with the University of the Sacred Heart (October 30, 2003–April 22, 2024).

https://www.instagram.com/moriokashoten/?hl=jaSogo Hiraiwa

Editor/writer

Born 1990 in Takayama, Gifu. Freelance editor and writer contributing regularly to literary, cultural, and fashion magazines. Also involved in planning and editing books, including the Japanese edition of Octavia E. Butler’s Bloodchild and Other Stories (trans. Hikaru Fujii). Translator of Virgil Abloh’s Dialogues (Adachi Press).

https://www.instagram.com/sogohiraiwa/Nathalie Cantacuzino

Photographer

Born in Stockholm, Sweden. Studied Japanese culture and photographic technique in Tokyo. Shoots in genres ranging from fashion to documentary and lifestyle.

https://www.instagram.com/nanorie/