銀座――この魅力的な街は、多くの人々にとって、特別な瞬間や記憶に残る場所となっています。親に手を引かれて足を踏み入れたデパート、マスターのこだわりを感じる喫茶店、初デートで訪れたレストラン。どれもが、この街の独特の雰囲気と結びついています。

連載「銀座・メモワール」では、森岡書店代表、森岡督行さんがナビゲーターとして登場します。多様なゲストが織りなす銀座の豊かな物語を共有し、銀座の多面性とその普遍的な魅力に焦点を当てます。連載を通じて、銀座の隠れた魅力と多彩なストーリーに触れ、新たな価値を一緒に発見しましょう。

花士(はなのふ)の珠寳(しゅほう)さんをゲストに迎えた連載「銀座・メモワール#4」。前篇では、銀座のギャラリーで目撃した歴史的な会話や、草木の“声”を聞き分ける指先の経験知について伺いました。後篇は、10年間にわたる銀閣寺(慈照寺)での超現実的な生活や7割で止める美学について。

▼前篇はこちらから

“室町時代”に住み、足利義政と対話した10年間

森岡 お話を聞いていて、以前インタビューで、つねに足利義政と対話をされているとおっしゃっていたことを思い出しました。足利義政は500年以上前に……

珠寳 1490年に亡くなられています。私は慈照寺で義政時代のお花を再考するというミッションをいただいて、10年間花方として室町の花文化を研究していたんです。文献や絵図もほとんど残っていないので、当時のお花を勉強するよりも、和歌や能楽といった中世の芸術やその土台にある禅の考え方を知ることで花の理解を深めていくわけです。それらを解釈する際に、自分の好みを入れるわけにもいきませんから、義政だったらどちらを好まれたかというのをひとつの指針にしたんです。それで、室町時代にいるつもりでお寺では義政と対話をするという10年間を過ごしました。自分でも妄想じみていると思わなくもないですけど、お寺のなかでのお仕事だったので、そういう生き方が可能だったんです。

森岡 500年以上前につくられた空間で暮らし、現代の情報を遮断して、そこに室町時代の情報を流入させると、タイムスリップのような体験ができたということですよね。

珠寳 そうです。

森岡 お聞きしたいのは、そのときに室町の光はどうだったのかなと。今よりずっと立体的だったのではないのかと想像します。

珠寳 電気はありませんから、自然光ですよね。書院は片側から光が入ってくるようなつくりになっているのですが、光が当たる方にお花の見どころを向けて飾る。例えば奥の方、庭がある方から光が入ってきて……

森岡 想像しただけでも、別の世界ですね。向こう側の世界を見るような。

珠寳 なので、今もお稽古をするときは、できるだけ電気はつけずに自然光でお花を見てくださいと申し上げるんです。お花そのものを見せるんじゃなくて、花が立ち上がったことによってそれまで感じなかった気配をその空間に生み出す。それが日本の「いけばな」だと思います。

森岡 一種のインスタレーションに近いですよね。

珠寳 そうだと思います。花一輪が空間にあることで、人の意識に作用して空間全体を感じることができる。

森岡 お花を理解するために義政と対話を続けているということでしたが、きっと特定の“一人”を指針にするのが大事なんでしょうね。

珠寳 私の場合は、当時の将軍さまでしたが(笑)。相手のハードルが高ければ高いほど、自分も一緒に引き上げてもらえる気がします。これは、時代や流行に左右されない勉強方法だと思います。

森岡 なるほど。でも、義政に裏切られたことはないんですか?

珠寳 「どうしてですか?」と尋ねたことはありました。慈照寺の花方を始めて10年目に、お寺での活動がストップしてしまったんです。そのときは本気で怒りました。義政命(いのち)でしたから(笑)。でも、それはシャバの時間軸で考えてしまっていたなと後になって反省しました。元々、慈照寺でのお花のプロジェクトは自分ひとりではとてもやりきれないし、100年後、3代目くらいになって初めてスタート地点に立てるかもしれないという考え方でいろいろ計画していたんです。その地ならしをするのが、自分の役割だろうと。

森岡 3世代先のために仕事をする。確かに銀座のテイラーにもそのような観点があります。

珠寳 当時は活動がストップすることに対して「どうして?」と強く思いましたが、今年、お寺を出て10年目なんですけれど、今は私に必要な10年であったとわかります。だから義政公との対話はこれからも続いていきます。

7割で止める美学

森岡 初歩的な質問ですが、足利義政がお花の文化に与えた影響はどういうものなんでしょうか。その前からたて花、いけ花の文化はあったんですか?

珠寳 そうですね、花を「立てる」という言葉は平安時代にも見られます。ただ様式としてのたて花を指しているのではないです。室町時代から花は「立てる」もので、そこから「いける」や「なげいれる」という花の様式も出てきます。義政公の時代に絞っていえば、いけ花が確立する前に“座敷を飾る”文化がありました。座敷を飾る目的は、イベントがあり客人を招く際に、唐物(その当時貴重な舶来品)を見せて美しく力を誇示することが目的だったようです。だから、唐物の絵画、器物、植物などを気合いを入れて飾る専門の職方も必要でした。日本に生息しないオウムやイヌやネコなどの動物も“唐物”として珍重されていましたね。ですから花は器ありき、唐物の器を引き立てる役割だったんです。

森岡 花は後からなんですね。

珠寳 そうです。義政のおじいさんにあたる義満の頃は特に、闘茶(とうちゃ:茶の味を飲み分けて競う遊び)や婆娑羅(ばさら:派手な人目を引くようなふるまい)のように、自分の力を「どうだ!」と誇示する雰囲気が強いのですが、義政の時代までくだると、ある美意識をもって座敷を飾り、ひとつの美しい世界をつくることに主眼が置かれていたように思います。

森岡 それはなぜなんでしょうか?

珠寳 義政の貴族的な美意識、教養の深さからだと思いますが、応仁の乱という動乱期を経て、足利家の権力や経済力が弱っていたことも影響すると思います。有事のときに東山にこもってお茶やお花をしながら優雅に過ごしていたという批判的な見方もありますけど、乱世はどうにもできないから、美に一筋の希望を見出しておられたんじゃないかなとも解釈できます。だからこそ、いちばん大切な部屋に「同仁斎」と名前をつけた。

森岡 どうじんさい?

珠寳 義政が晩年多くの時間を過ごした四畳半の小間で、今は国宝になっているのですが、名前は「聖人一視而同仁」(聖人君主たる者、一視にして同仁し、生きとし生けるものを分け隔てなく同じように視る)という言葉にちなんでいます。そうした義政の精神性や美意識から、茶や花、香の礎が育まれていったのだと考えています。

森岡 義政の時代は今の状況と被りますね。乱世ですし、経済的にも弱っている。

珠寳 そうですね。でもそういう時代だからこそ、見えなかったことがよく見えるようになるといいなと思います。満々にあると見えないものが、ないから逆に大切なものが見えてくる時期かもしれませんね。

森岡 今のお話とつながるかわかりませんが、粋についてもお聞きしたいです。銀座は粋の街だといわれているので、自分もよく粋ってなんだろうと考えるのですが、珠寳さんのお花にある不完全性というか、7割くらいで留めておく姿勢が粋とは何かを考えるうえでヒントになる気がしました。

珠寳 3割はお任せするみたいなね。義政も“ない”ことを貧しいと捉えるのではなく、それをいかに美しさに転換するのかを考えていたように思います。そこにすばらしい教養があった。私は7割で止めると思っていても、まだ葛藤があります。もう少し手を加えたほうがいいんじゃないかと思うときもあって。やりきらないのは意識していても難しいですね。

森岡 7割で止めるのは、例えば、どんなときに?

珠寳 お花をあと一手加えたいなと思うあたりで止めます。もしかしたら、一手加えたほうが形としてはバランスが取れるかもしれないという思いがあっても、欠けた「間」をのこして、見る人の3におまかせして完成させる。だから答えはひとつではない世界。そんなやりとりの余裕が、もしかしたら粋につながるのかもしれません。

珠寳 花士

2004年から2014年まで慈照寺(銀閣寺)にて初代花方を務め、義政公時代の「座敷飾りの花」「室礼」の顕彰、江戸中期に創流された「花術 無雙眞古流」の再生に10年間従事。慈照寺研修道場にて講座の企画、運営をし、「平和と文化」をテーマに国際交流を企画、実施。

2015年に青蓮舎を設立し、草木に仕える花士として、大自然、神仏、人に花を献ずることをライフワークとし、花朋の会では花を通して豊かな生活時間を提案している。また、能楽、現代美術、音楽、工芸、建築など、伝統から現代の国内外のクリエーターと協働。

2024年からは一般社団法人游神会を設立し、代表理事を務める。精神をおおらかに遊ばせた室町時代の阿弥系のたて花から時代を追って、「いけばな」の精神性、美と術を探求し、記録をとる事業を主軸とする。いけばなのはじまり、成立、展開、関連する学問、芸術、芸能などを知る場を作り、次代をになう人材育成に努める。主な著書:

『銀閣慈照寺の花 造化自然』(淡交社)

『一本草』(徳間書店) 他

森岡 督行

1974年山形県生まれ。森岡書店代表。文筆家。『800日間銀座一周』(文春文庫)、『ショートケーキを許す』(雷鳥社)など著書多数。 キュレーターとしても活動し、聖心女子大学と共同した展示シリーズの第二期となる「子どもと放射線」を、2023年10月30日から2024年4月22日まで開催する。

https://www.instagram.com/moriokashoten/?hl=ja平岩壮悟

編集者/ライター1990年、岐阜県高山市生まれ。フリーランス編集/ライターとして文芸誌、カルチャー誌、ファッション誌に寄稿するほか、オクテイヴィア・E・バトラー『血を分けた子ども』(藤井光訳、河出書房新社)をはじめとした書籍の企画・編集に携わる。訳書にヴァージル・アブロー『ダイアローグ』(アダチプレス)。

www.instagram.com/sogohiraiwaナタリー・カンタクシーノ

フォトグラファー

スウェーデン・ストックホルム出身のフォトグラファー。東京で日本文化や写真技術を学び、ファッションからドキュメンタリー、ライフスタイルのジャンルで活躍。https://www.instagram.com/nanorie/

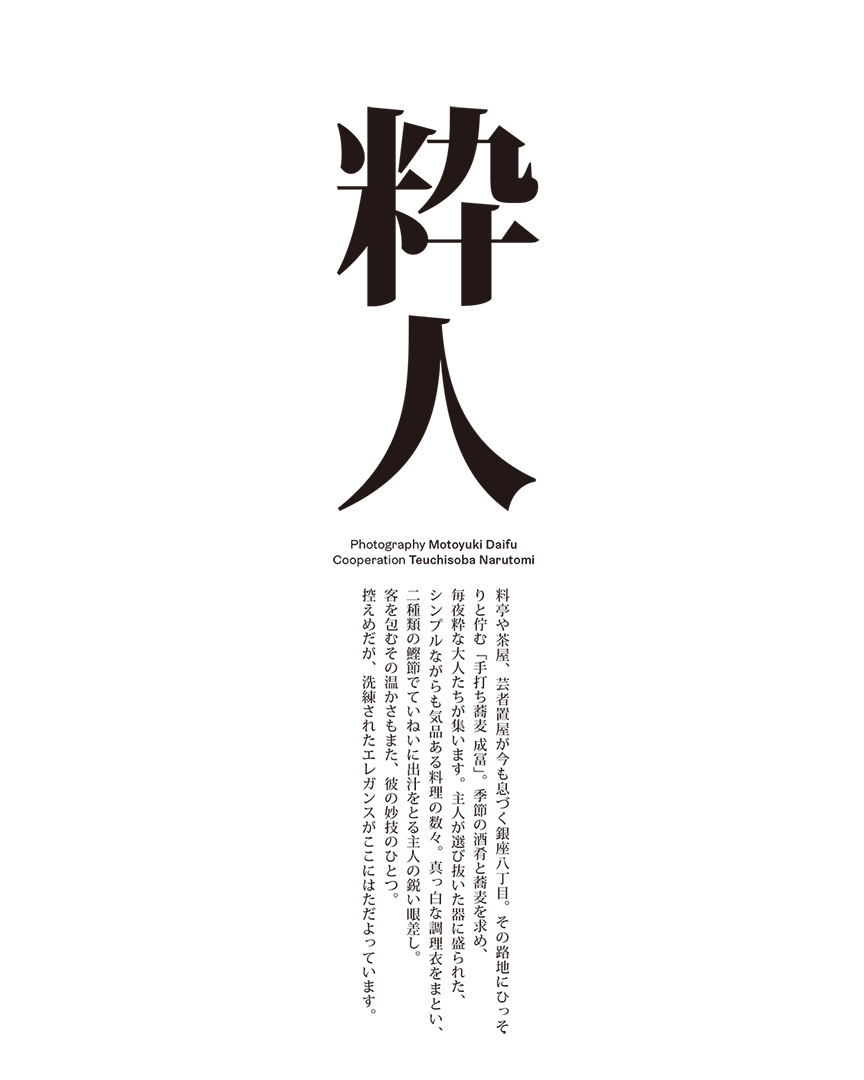

Ginza Memoir #4 Part 2 Shuho "The Beauty of Absence, Born in Turbulent Times"

2024.10.17

Text / Sogo Hiraiwa

Photo / Nathalie Cantacuzino

Ginza is a fascinating town, frequently linked with special moments and fond memories. Visits to department stores while holding tightly to a parent’s hand, afternoons in old-fashioned cafés run by one-of-a-kind characters, first dates in special restaurants . . . Ginza is a place like no other.

Hanatsubaki’s “Ginza Memoir” series, hosted by Yoshiyuki Morioka of the iconic Morioka Shoten bookstore, explores the multifaceted nature and universal appeal of Ginza through interviews with guests from a wide variety of fields. With Morioka as guide to Ginza’s hidden charms and diverse narratives, new discoveries await around every corner.

Our fourth guest for “Ginza Memoir” is Hananofu Shuho. In the first part of our interview, Shuho told us about the historic conversation she witnessed at a Ginza gallery and her experience of “hearing” the flowers through her fingers. In this second part, we discuss the dreamlike lifestyle she led at Jishoji, the Temple of the Silver Pavilion, and the art of stopping at the seven-tenths mark.

(Read Part 1 here.)

Ten Years in Dialogue with Ashikaga Yoshimasa

Morioka: In a past interview, I recall that you said you were always in dialogue with Ashikaga Yoshimasa. And yet he lived more than 500 years ago . . .

Shuho: He died in 1490, yes. I spent ten years as general manager of flower affairs, or hanagata, at Jishoji, studying the flower culture of the Muromachi period [1336–1573]. My mission was to rethink the way of flowers as it existed in Yoshimasa’s time. Very few texts or diagrams survive from that period, so rather than studying the flowers of that period directly, I deepened my understanding of flowers by learning about medieval arts like poetry and Noh, and the Zen philosophy that served as their base. It wouldn’t have done to allow my personal preferences to affect my interpretations, so I took “What would Yoshimasa prefer?” as my guide. And so I spent ten years at the temple, immersed in the Muromachi Period and in dialogue with Yoshimasa. Even to me, it sounds almost like a fantasy, but it was possible because my work was done within the temple.

Morioka: Living in a space built more than 500 years ago, cutting yourself off from contemporary information in favour of the ideas of the Muromachi Period—an experience somewhat like time travel.

Shuho: That’s correct.

Morioka: I’m curious to learn more about the light of the Muromachi period. I imagine it created a much stronger sense of space than today.

Shuho: There was no electricity, so all light was natural. Shoin rooms were made so that light would enter from one side, and they were decorated with flowers arranged so that their best features were on the side with the light. For example, light might enter from the back of the room, or the side facing the garden.

Morioka: Just imagining it feels like a different world. Like seeing the world beyond.

Shuho: When I hold lessons, I avoid electric light as much as possible and instruct my students to view the flowers in natural light. Japanese ikebana is not, in my opinion, about showing the flowers themselves, but rather about arranging them to create a presence in the space that was not there before.

Morioka: Like a kind of art installation.

Shuho: I think so. A single flower has an effect on people’s consciousness that encourages a new awareness of the space as a whole.

Morioka: You developed your understanding of the flowers in dialogue with Yoshimasa. I suppose taking a single, specific “person” as guide is key.

Shuho: And my guide was a shogun! But the higher the hurdles you face, the more you are raised up yourself, together with the other person. I see this as a method of study unaffected by the times or the trends of the age.

Morioka: Did Yoshimasa ever steer you wrong?

Shuho: At times I did ask, “Why?” In my tenth year as hanagata at Jishoji, my activities at the temple stopped. I was truly angered by this, as Yoshimasa was my life! But I later realized that this was because I was thinking in terms of time spent in the outside world. Complete the temple’s flower project by myself had never been a realistic goal, and all my original planning had been based on the idea that, a hundred years from now, perhaps the third hanagata would perhaps be ready to stand at the starting line. My role was to pave the way.

Morioka: You did your work for the sake of someone three generations in the future. Ginza’s tailors have a similar perspective.

Shuho: At the time, I couldn’t understand why my activities had stopped. But I’m currently in my tenth year since leaving the temple, and I understand now why these ten years were necessary. I plan to continue my dialogue with Yoshimasa.

The Art of Stopping at the Seven-Tenths Mark

Morioka: If you’ll pardon the elementary question, what exactly was Yoshimasa’s influence on the way of flowers? Did the culture of tatehana and ikebana predate him?

Shuho: Well, the use of the word “standing” (tateru) for flowers dates back to the Heian period [794–1185], but at that time it didn’t refer to tatehana as a style. From the Muromachi period, we see a development of words for floral arrangement styles, from “standing” to “imparting life” (ikeru) and “casting” (nageireru). If we restrict the discussion to Yoshimasa’s time, before ikebana developed as such, there was a culture of “decorating rooms.” The goal of this decoration appears to have been to demonstrate power in a beautiful way using karamono (items imported from overseas, which were very precious at the time) that were put on display for invited guests. To properly decorate with these karamono, which included pictures, ceramics, plants, and so on, specialists were needed. Animals not found in Japan, like parrots, cats, and dogs, were also prized as karamono. The vessels thus predated the flowers, which were needed to show karamono to best effect.

Morioka: The flowers came later. I see.

Shuho: That’s right. Particularly during the time of Yoshimasa’s grandfather Yoshimitsu, people preferred brasher, bolder displays of power. This gave rise to things such as tocha (competing to recognize different kinds of tea based on flavour) and basara (brash, eye-catching behaviour). By the age of Yoshimasa, however, the chief goal seems to have been to decorate a room based on a certain aesthetic sensibility, creating a unified world of beauty.

Morioka: Why do you think things changed in that way?

Shuho: I believe it came from Yoshimasa’s noble aesthetic sensibility and depth of learning, but the weakening of the Ashikaga family’s authority and financial power during the turbulent Onin War period [1467–1477] probably also had an effect. Some take a critical view of the idea of spending times of crisis safely hidden in Higashiyama, idling away the days with tea and flowers, but my interpretation is that Yoshimasa recognized his powerlessness in the face of the age’s turbulence, and found a ray of hope in beauty. That is exactly why he called his most important room the Dojinsai.

Morioka: “Dojinsai”?

Shuho: It’s a small 4.5–tatami mat room where Yoshimasa spent a great deal of time in his later years, and a national treasure today. The name comes from a famous aphorism, roughly translating to “The sage views all things with equal benevolence.” I believe that the foundations of tea, flower arranging, and incense were cultivated under this spirit and aesthetic exemplified by Yoshimasa.

Morioka: Yoshimasa’s age is similar to our own in some ways. Turmoil, financial crises . . .

Shuho: Yes. But precisely because we live in such an age, I hope that we will come to see things that were invisible to us before. This may prove to be an age when things that went unseen when abundant reveal their importance by their very absence.

Morioka: I’m not sure if this is related, but I would like to ask you about the aesthetic ideal known as iki. Ginza is said to be an iki town, so I often wonder what iki means exactly. It seems to me that your use of imperfection in your arrangements, the attitude of “stopping at the seven-tenths mark” of which you have spoken, could offer some clues in this regard.

Shuho: The final three-tenths are up to the viewer. Yoshimasa didn’t take absence as impoverishment, either; rather, he seems to have thought about how one might turn it into beauty. There was a wonderful lesson there. Even if I mean to stop at the seven-tenth mark, I still find myself torn. I wonder: Wouldn’t it be better to do a little more? It’s difficult to leave something undone, even intentionally.

Morioka: What kind of things do you “stop at the seven-tenths mark”?

Shuho: I stop working on my arrangements around when I start thinking Just one more change. Even if I suspect that one more change would result in a more balanced form, I leave that absence, that ma, as it is, and let the viewer supply the final three tenths and complete the work. This is a world with more than one answer. That kind of relaxed exchange might be connected to iki as well.

Hananofu Shuho

From 2004 to 2014, acted as first general manager of flower affairs at Jishoji (the Temple of the Silver Pavilion), spending a decade showing how flowers were used to decorate rooms in the age of Ashikaga Yoshimasa and reconstructing the Muso Shinko school of flower arrangement founded in the mid-Edo period. Planned and hosted workshops at the temple’s research centre, and planned and executed international exchanges around the theme “peace and culture.”

In 2015, established the Seirensha and embraced her life work as a hananofu of offering flowers to nature, the divine, and people, promoting richer lifestyles through flowers via Kaho no Kai gatherings. Also collaborates with traditional and contemporary creators in Japan and around the world in fields such as Noh, contemporary art, music, crafts, and architecture.

In 2024, established the Yushinkai NPO and became its representative director. The organization is chiefly concerned with tracing the history of tatehana from the Ami tradition of the Muromachi Age, which allowed the spirit to play in serenity, and researching and recording the spirituality, art, and technique of ikebana. Strives to create opportunities for learning about the beginning, establishment, and development of ikebana, along with related fields of study, art, and performance, and to cultivate the next generation of practitioners.Major published works:

Flowers of Jishoji of the Silver Pavilion: Creative Nature (Tankosha)

Ippongusa: A Single Stem (Tokuma Shoten)https://www.hananofu.jp/ja/top/

Yoshiyuki Morioka

Born 1974 in Yamagata. Head of the Morioka Shoten bookstore. Writer. Published books include Around Ginza in 800 Days (Bunshun Bunko) and Forgiving the Shortcake (Raichosha). Also active as an art curator, with recent shows including Children and Radiation, the second stage of an exhibition held jointly with the University of the Sacred Heart (October 30, 2003–April 22, 2024).

https://www.instagram.com/moriokashoten/?hl=jaSogo Hiraiwa

Editor/writer

Born 1990 in Takayama, Gifu. Freelance editor and writer contributing regularly to literary, cultural, and fashion magazines. Also involved in planning and editing books, including the Japanese edition of Octavia E. Butler’s Bloodchild and Other Stories (trans. Hikaru Fujii). Translator of Virgil Abloh’s Dialogues (Adachi Press).

https://www.instagram.com/sogohiraiwa/Nathalie Cantacuzino

Photographer

Born in Stockholm, Sweden. Studied Japanese culture and photographic technique in Tokyo. Shoots in genres ranging from fashion to documentary and lifestyle.

https://www.instagram.com/nanorie/